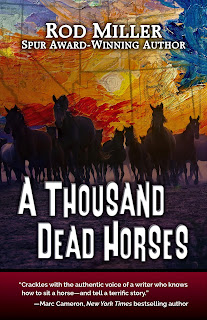

After being bedridden for six months because of the coronavirus

pandemic, A Thousand Dead Horses is finally on the market.

By happenstance, like Pinebox Collins, the novel that

precedes it, it features a main character with a wooden leg. But I had no

choice this time. The book is based on a historic horse-stealing expedition

from the 1840s, and one of the primary perpetrators of that adventure was famed

mountain man Thomas L. “Pegleg” Smith. Honest.

Besides Pegleg Smith, the story features other characters from

history including mountain men “Old Bill” Williams and James Beckwourth, and

Ute leader Wakara. The horses and mules they stole are real, too—but I don’t

know their names.

Marc Cameron, New York Times bestselling author of the

Jericho Quinn political thrillers, the Arliss Cutter crime novels, and several of

the Tom Clancy Jack Ryan novels, says, “A Thousand Dead Horses crackles

with the authentic voice of a writer who knows how to sit a horse—and tell a

terrific story. Fire embers snap, saddle leather groans—and the richly drawn

characters pull you along with them on their adventure.”

The story, based on history from the Old West, will take you from Santa

Fe to California and back again on the Old Spanish Trail.

Ride along.